Tractors didn’t just replace horses, they rewired agriculture.

Each design leap from steam powered to gasoline made a major impact. To the farm they brought mass production, row-crop geometry, the three-point hitch, diesel + hydraulics, 4WD frames, rubber tracks, CVT transmissions, GPS autosteer, and now electric + autonomy—made farming faster, safer, more precise, and more profitable.

If you love clean rows, straight passes, and machines that turn dirt into dinner, you’re in the right place. Tractors.net is a living guide to where farm power came from, where it’s going, and how to choose the right iron (or electrons) for your acres.

Before the roar: muscle power meets physics

For most of human history, fields ran on hay, oats, and grit. Animal traction limited speed, depth, and acreage. Weather could steal entire weeks; fatigue stole the rest. Early steam traction engines proved you could trade oats for boilers, but they were heavy, thirsty, and… a little terrifying. The idea was right—mechanize the pull—but practicality needed a smaller, cheaper, easier start-and-go package.

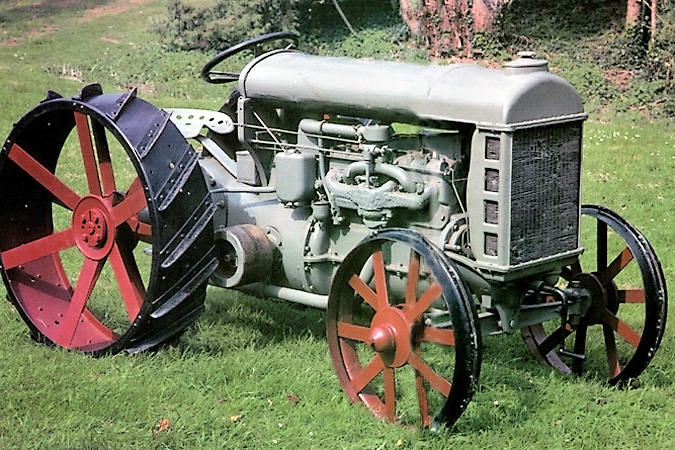

Mass adoption: the Fordson moment

Enter the Fordson Model F (late 1910s–1920s). Built like a Model T for fields, it pushed tractors from specialty to standard. Gasoline power, castings that simplified assembly, and a price farmers could actually reach—this is when “tractor” stopped being a neighbor’s rumor and started being your next purchase. The payoff: more acres per operator and a path to mechanized tillage and planting on family farms, not just estates.

Farmall invents the row-crop template

The International Harvester Farmall “Regular” (1920s) made tractors nimble. High-clearance frames, narrow fronts, and a driver’s seat aligned with crop rows let farmers cultivate without crushing plants. Suddenly, geometry mattered as much as horsepower. Weeds lost, yields won, and the “row-crop tractor” became a whole category.

Implements go smart: Ferguson’s three-point revolution

Harry Ferguson didn’t sell just a tractor; he sold an interface. The Ferguson TE-20/TO-20 (’40s) popularized the three-point hitch with draft control, turning implements into extensions of the tractor. Hookups got faster, depth control got automatic, and a universal standard unleashed an implement ecosystem. The tractor became a platform, not just a puller. That idea still rules every yard, auction, and dealer lot today.

Diesel + hydraulics + human factors: the 4020 era

By the 1960s, diesel torque and better hydraulics made long days productive days. The John Deere 4020 is the poster child: reliable diesel power, serious hydraulic capacity, and transmissions (hello, Power Shift) that didn’t beat operators up. Competitors were pushing, too—think Allis-Chalmers WD/WD45 era live power concepts and Massey Ferguson 35-class tractors popularizing dependable utility platforms. Cab design started to matter: heaters, ventilation, then air conditioning and soundproofing. Farmers didn’t just endure the work; they could actually think during it.

Big acres, big frames: articulated 4WDs pull the horizon closer

As farms scaled, so did frames. Steiger and Versatile 4WDs (’60s–’70s into the ’80s) spread power across big rubber and hinged in the middle to turn that mass. These units pulled wider tools, cut field passes, and attacked prairie-scale acres. The conversation changed from “can we pull it?” to “how few passes can we get this done in?” Soil compaction became a real design constraint, pushing tire tech and ballasting strategies forward.

Float and grip without the ruts: the rubber-track era

The Challenger 65 (mid-’80s) brought rubber tracks to farm fields. Suddenly you could put down huge tractive effort while spreading weight, keeping speed, and working in marginal conditions. Today’s quad-track machines—John Deere 9RX, Case IH Steiger Quadtrac—extend that logic: flotation plus bite, with a turning radius that doesn’t eat half your field. Result: preserved soil structure, longer working windows, and fewer “park it, it’s too greasy” days.

Transmissions get brains: CVT changes how power feels

The Fendt Vario (’90s) made continuously variable transmissions mainstream at higher horsepower. No shift shock, perfect ground speed, and efficient power delivery across jobs—from creeper speeds in the transplant game to road speeds between fields. Other makers followed with their own CVT/IVT takes. Once you run one, it’s hard to go back; “right speed, right load” becomes a set-and-forget baseline.

GPS turns acres into data: autosteer, RTK, and section control

The late ’90s/early 2000s brought satellites into the cab. Systems like John Deere AutoTrac on 8-series tractors redefined straight. RTK guidance cut overlap, variable-rate maps reduced waste, and section control stopped applying inputs where they wouldn’t pay back. The operator became a system integrator: agronomy + machinery + software. Every pass left data behind; every new pass could learn from it.

Comfort as productivity: Magnum, 8000-series, and modern cabs

Ergonomics turned into ROI. The Case IH Magnum line and the Deere 8000/8R families showed that control layout, visibility, suspension seats/axles, and low cabin noise reduce errors and fatigue. Fewer mistakes at 2 a.m. during plant or harvest is not a “soft” benefit; it’s the difference between making the window and missing it.

Alternative power arrives: electric, methane, hybrid

Not every job needs 500 diesel horses. Monarch and Solectrac electric utilities thrive in orchards, vineyards, campuses, and barns where quiet and zero tailpipe emissions matter. On the big-iron side, concepts like

Autonomy and swarms: the next operator is a fleet manager

Autonomy is already creeping into tillage, planting, and cart-chasing. Major OEMs (think Case IH and John Deere) are testing machines that can work all night, ping you when conditions change, and adjust rates on the fly. Some visions go small: swarms of light electric units to minimize compaction. Others go big: supervised driverless versions of the tractors you already know. Either way, the role shifts from steering wheel to dashboard—oversight, logistics, and agronomy decisions guided by live data.

The through-line

From the Fordson’s price tag to the 4020’s hydraulics, from the Farmall’s geometry to the Vario’s smooth pull, from rubber tracks to GNSS corrections—the tractor’s “glow-up” is really agriculture’s glow-up. Each generation pushed the same mission forward: do more, do it better, protect the soil, protect the operator, and make the numbers pencil out.

This is Tractors.net: part museum, part buyer’s guide, part future lab. Kick the tires, dive the timelines, and bring your questions. The next pass starts here.